Op-Ed: From Fossil Fuels to Your Lungs

The Thames above Waterloo Bridge by JMW Turner (1)

Starting in Europe in the 18th century, humans began using fossil fuels for energy. Rapid industrialisation lifted whole continents into unbridled productivity, but this created pollution; air became fetid and murky. Turner captured this in some of his paintings of England; skylines of cities, and the subjects in the images are obscured, lost in a smoggy smudging of air. The far banks of the river Thames disappear into a hazy soup.

In 1952, London saw the effect of this unrecognised danger when still, cold weather made the pollutants ejected from cars, industry and coal burning linger. The Great Smog sat over London; pollution being breathed in by the people milling about town. Within 4 days, an estimated 4,000 to 12,000 people died and 100,000 were made ill (2). A few years later, progress was made to reduce the burden of disease of poor air quality and air pollution, in a major step for population health.

Air pollution takes on many forms. The tell-tale signs of pollution aren’t always as ominous as obscured buildings and killer smog. Sometimes it is a warm haze in the air that paints everything in a golden hue. Sometimes it is a smoky softness that hangs over a city. Whichever form, air pollution is always dangerous, with no safe level of exposure (3). Two main groups of air pollution exist. Gases come from a variety of sources, including transport, industry, soil, agriculture, and environmental conditions, and include ozone, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. Aerosols are grouped under one title: Particulate Matter (PM). PM is grouped by size in micrometres: PM10, PM2.5, and PM0.1. The different sizes lead to different effects; when breathed in, these particles, as they get smaller, can deposit further into the air sacs where oxygen and carbon dioxide move between blood and air.

When entering into the body, the immune system recognises these particles as foreign, and triggers inflammation. The cascade this starts can lead to heart attack and stroke. Besides these though, air pollution can also contribute to chronic lung diseases, cancer, diabetes, dementia, low birth weight, high blood pressure, and mental illness, with children being more susceptible to the effects of pollution (4)(5).

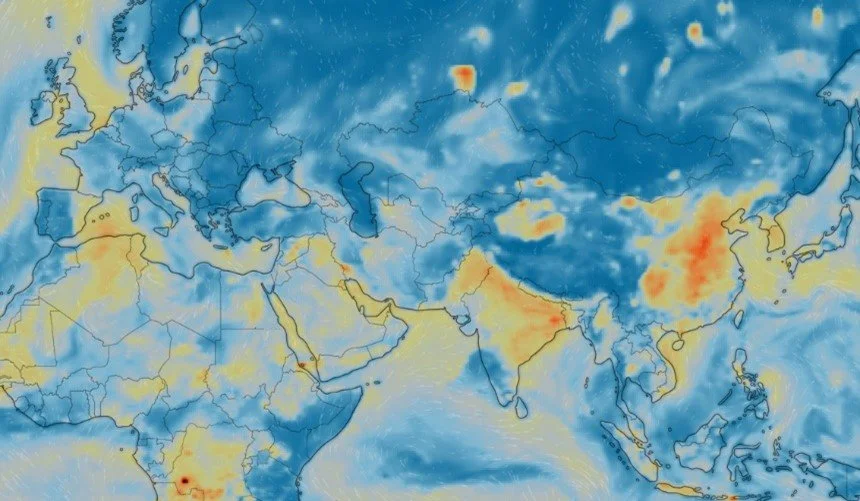

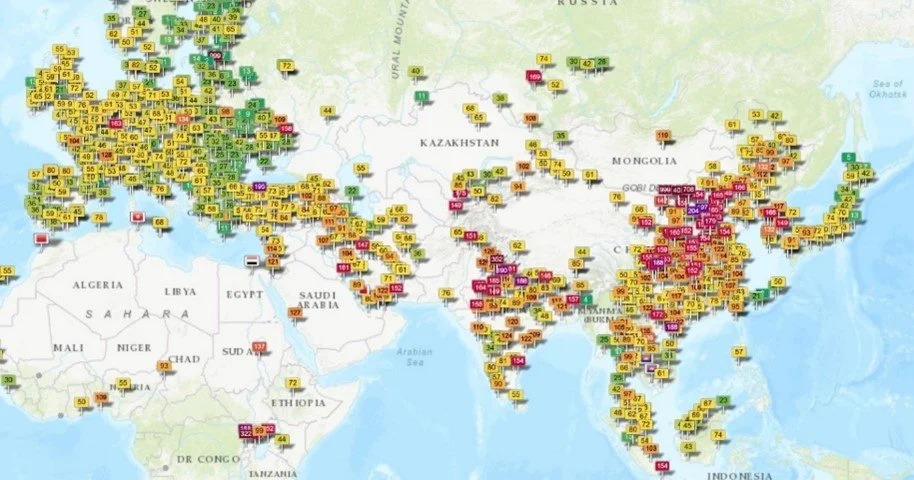

Air quality and pollution varies due to a number of factors, and the factors are unequally dispersed globally. In parts of Europe, environmental, energy and transport policies mean that the air can be relatively clean. In other parts of the world however, heavy industry and transport, lack of regulation and unfavourable environmental conditions can mean that pollution is inescapable and pervasive. In a lose-lose situation, poor outdoor air quality can be compounded by poor indoor air quality and can shorten lives by decades.

Air Quality Guidelines from the WHO (6).

The World Health Organization (WHO) states guidelines which air pollution exposure should not exceed to protect health, and they have recently released new guidelines which set lower limits than previous (7). Many locations regularly exceed these figures through a normal day, and globally 92% of people live in areas that exceed these guidelines (8). Random sampling at the time of writing showed the level of PM2.5 exceeded the WHO limits in most European countries (9). An Air Quality Index (AQI) can also assess air quality and operates on a scale considering multiple pollutants that is country-specific (4).

The WHO states air pollution is a “major environmental risk to health” (9); 8.7 million people die prematurely per year (11). This is more than double the official death toll for the Covid-19 pandemic at the time of writing (12). Others have made this comparison between the pandemic, and the overlooked pollution pandemic, stating that what makes pollution risk so dangerous is its physical and political invisibility, its relative normalisation (8). Deaths are somewhat accepted as an unchangeable, inevitable outcome. More than 90% of these deaths are in low- and middle-income countries (8). Global analysis of exposure and excess mortality showed that the annual mean PM2.5 concentration in East Asia was just above 50, ten times the current WHO guidelines (8). At this exposure, it was reasoned that 30% of all deaths were related to air pollution; this is higher than the global average of 20% (8).

Sample map of PM2.5 levels at the time of writing. Courtesy of windy.com (10)

There is hope. While polluted areas were becoming more polluted, less polluted areas were becoming less polluted (10). People, cities, governments and organisations are starting to realise the massive impact of air pollution on society in some regions. It has helped that a very high-profile subject, Climate Change, is intimately linked to air quality, and efforts to reduce and legislate against an unstable climate, usually also work to improve air quality. Regulation and innovation are paving the way for more equitable, sustainable and air-friendly places to live; some cities are becoming greener, less energy intense and working to promote active and public transport. Energy production is shifting to focus on renewable energy, and away from fossil fuel combustion. Private innovation is raising awareness and informing people about the dangers, such as in London, where an app can inform your bicycle commute to account for local air quality (13). Transport is slowly becoming cleaner, with many European countries looking to a future without petrol and, importantly, diesel (the most significant source of PM0.1) (14).

Sample map of AQI at the time of writing. Courtesy of World Air Quality Index (4)

The United Nations is pushing forward with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with air quality being linked to the Goals 3, 7, 11 and 13. The state of the atmosphere has received intense interest recently also with the recent publishing of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report about the state of the climate ahead of the COP26 conference in Glasgow in November. Given the inter-relationship between air pollution and Climate Change, the current level of discourse in governments, in the media, and in the societies of the planet are reassuring. We are seeing the widespread acceptance that the climate is changing due to human activity, and that more time is lost deciding what to do rather than acting, drawing us closer to irreversible climate changes. The time is ripe for action on air pollution, with society ready to embrace a future with cleaner air. The time is now to put pressure on individuals, organisations and governments to make sweeping changes to ensure the health of the planet going forward.

While sweeping changes from corporations, organisations and governments will be integral to improving the state of the climate, individuals can reduce air quality impact in their own way, such as using active or public transport for travel, using renewable sources of energy for electricity and travel (such as electric cars) and voting with their wallets to favour products and companies that have proved there are working to reduce their environmental impact. Information is available for those inspired to change, such as through supranational organisations, such as the United Nations Environmental Programme (15) and the One Planet Network (16), but also through NGOs such as Global Action Plan (17), and local Environmental Protection agencies.

Those concerned with the state of the planet, the environment, and the health of the people living on the planet should fight for clean air, and advocate for the reduction of air pollution in all forms. It is a dangerous, unnecessary harm that have been allowed to run rampant. The danger in the air isn’t always as ominous as fiery skies, gloomy horizons or obscured buildings. Memories from my childhood are filled with Australian summer days where the warmth seemed to hang in the air. Trips to Asian cities with a cold, light smog, or dusty afternoons in India and the Middle East, where the environment let me know that I was away from home on an adventure. Bright orange sunsets over endless hills exaggerating the layers of the landscape in the Balkans. While these memories are now seen in a different light, there is hope that the future will be cleaner, better and more sustainable. The timing has never been better to make the change.

The Sustainable Development Goals (18)

Orange Hills in Prizen, Kosovo.

This Op-Ed was written by Cale Lawlor.

With a background in Medicine and Public Health, Cale believes that health, access, and equality are essential for all people. Cale is dedicated to changing the social determinants of health that prevent people from living in optimum health, not just being free from disease, but also have clean air to breathe, clean water to drink, in an environment free of conflict, discrimination, and inequity.

References

Public domain, under Creative Commons License.

Klein, C. The Great Smog of 1952. History.com. August 22, 2018. Retrived May 31, 2021, from: https://www.history.com/news/the-killer-fog-that-blanketed-london-60-years-ago

World Air Quality Index. World's Air Pollution: Real-time Air Quality Index. 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from: https://waqi.info

World Health Organisation. Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution – REVIHAAP Project. World Health Organisation. 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/air-quality/publications/2013/review-of-evidence-on-health-aspects-of-air-pollution-revihaap-project-final-technical-report

Laville, S. Air pollution a cause in girl's death, coroner rules in landmark case. The Guardian. December 16, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/16/girls-death-contributed-to-by-air-pollution-coroner-rules-in-landmark-case

Kukolj, S. There is no “safe level” of air pollution. Balkan Green Energy News. October 15, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from: https://balkangreenenergynews.com/there-is-no-safe-level-of-air-pollution/

World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. World Health Organization. 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345329

Solnit, R. There's another pandemic under our noses, and it kills 8.7m people a year. The Guardian. April 2, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/apr/02/coronavirus-pandemic-climate-crisis-air-pollution

World Health Organization. Outdoor (ambient) air pollution. 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health

Windy. Map with PM2.5. 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from: https://www.windy.com/-Menu/tools?cams,pm2p5,39.506,64.512,3

Vohra, K., Vodonos, A., Schwartz, J., Marais, E.A., Sulprizio, M.P. & Mickley, L.J. Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem. Environmental Research. April, 2021; Vol 195: 110754.

Worldometer. Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Cahill, L. The air pollution solution for cyclists - app claims to help London cyclists avoid the most polluted routes. Road.cc. June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from: https://road.cc/content/tech-news/air-pollution-solution-london-cyclists-274481

European Public Health Alliance. Tackling the health impacts of non-exhaust road emissions online webinar. Hosted and viewed June 3, 2021.

United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP). Consumer Information, including Ecolabeling. UNEP. No date. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/sustainable-lifestyles/consumer-information-including

One Planet Network. Sustainable Consumption and Production. One Planet Network. 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/SDG-12/sustainable-consumption-and-production

Global Action Plan. Global Action Plan's information resources and insights. Global Action Plan. 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from: https://www.globalactionplan.org.uk/knowledge-hub

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Disability. United Nations. ND. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/about-us/sustainable-development-goals-sdgs-and-disability.html